When I was small, I asked my mother to teach me how to do needlepoint. I had seen her working on needlepoint pieces as I grew up, and I wanted to know how it was done so I could make pieces like hers. (She was good enough at it to take prizes at the State Fair of Texas.) She refused. I believe she did so because I was already regarded as odd by my classmates, and she thought I didn’t need one more thing to make me different, and a target for picking-on.

So as it turned out, I had to wait until I was engaged before I found someone to teach me the basics of needlework. My then-fiancée (now my once-and-future wife) had no inhibitions about men doing needlework; as she pointed out, if Roosevelt Grier could do petit-point and command fancy prices for it because of the quality of his work (and not simply for the name association), there was no reason I shouldn’t do the same if I liked.

I began with cross-stitch, a form of needlework where the design or picture is formed by making stitches that cross over one another, hence its name. Cross-stitch comes in two kinds: stamped, where you follow a pattern already printed on the fabric, and counted, where you create the piece on a blank piece of even-weave cloth, by following a printed chart. Most people who do cross-stitch begin with stamped, because it looks easier than the continual attention that counted cross-stitch requires, and because it’s easier to follow someone else’s pattern, in the same way it’s easier to create a picture with a paint-by-numbers set than it is to begin with a blank canvas.

I became dissatisfied with stamped cross-stitch fairly quickly, because I found that no matter how good the kit purported to be, the printing was invariably crooked to the grain of the cloth, which makes for stitches of uneven size and shape. In short, stamped cross-stitch looks sloppy, do what you will. Counted cross-stitch avoids this problem by using any of a number of kinds of cloth with the threads woven in a regular, even pattern.

A number of my early counted pieces were “architecturals” (elevation drawings) of lighthouses found in the Chesapeake Bay, worked with two strands on 14-count Aida cloth; I’m now dissatisfied with the way they turned out, and one day may re-do some of them on a higher-count fabric working with one thread. I very much like the charts, but my execution simply wasn’t up to snuff.

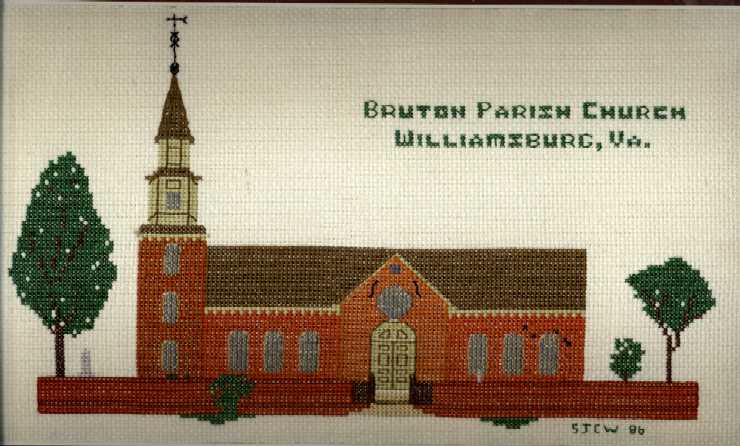

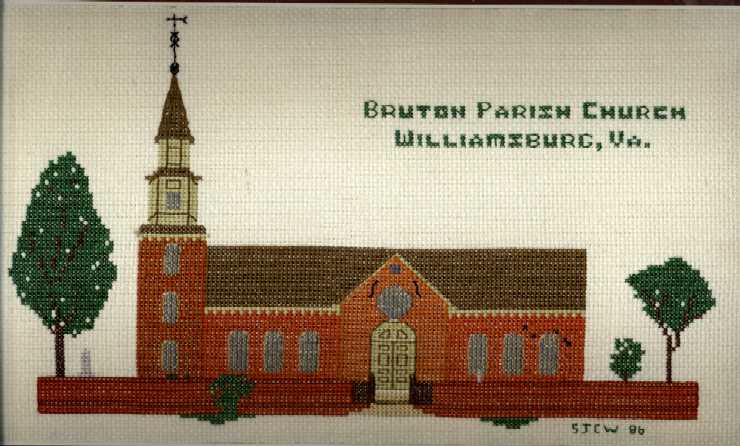

By the time I’d done the piece above, an architectural of the Episcopal church in Colonial Williamsburg, my technique was better, but it couldn’t make up for a less-than-inspired chart. It’s a perfectly adequate elevation view, as far as that goes, but no longer that interesting to me. This was about the last piece I worked on Aida; I had come to dislike the texture of the cloth, which I feel distracts the viewer’s attention from the picture itself. I also found I was dissatisfied with the look created by working with multiple strands of embroidery floss, and annoyed by the extra work involved in making sure the strands lay flat rather than twisting over one another, which gives, a rough, lumpy look to the work. Finally, I found what photographers have known all along—that enlarging an image makes it coarser; work in small sizes, and you can smooth out the roughness. And that, Best Beloved, was how I came to working on even-weave linen over one thread.

Most cross-stitchers who work on even-weave fabric do what’s known as working “over two;” that is, they stitch across two vertical or horizontal threads at a time. Hence, a piece worked on 28-count fabric (28 threads to the inch) over two comes out the same size as a piece worked on 14-count over one thread. This, however, wasn’t enough challenge. My mother, and her mother before her, and her mother before her, all worked at eighteen stitches to the inch or smaller, and I wasn’t about to be left behind. I began working with fabrics between 22 and 28 threads to the inch, and over one thread, rather than over two. This means a piece which would be six by eight inches worked at 28-over-two would be three-by-four when I was done with it, at 28-over-one.

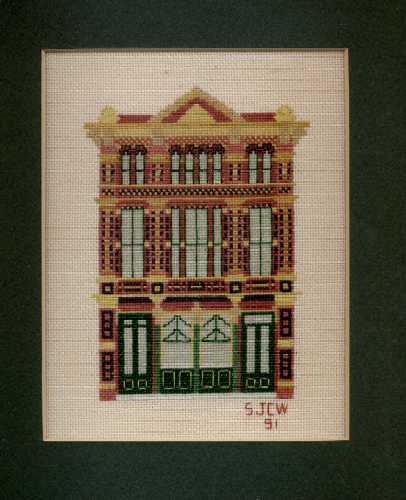

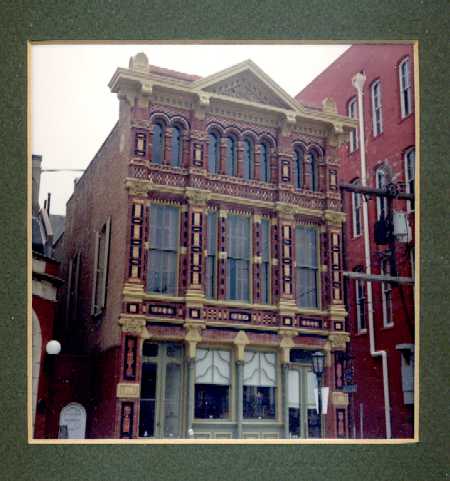

This project, the Trueheart-Adriance Building (1889), just off the Strand in downtown Galveston, was the first one I attempted after I gave up Aida cloth for even-weave linen and higher stitch counts. (A photograph of the building itself is at right, above, for comparison.) The building is high Italian Baroque Revival, with tons of decorative brickwork that translated into pure misery to make into needlework. I worked it on 28-count Lugana over one, and for most of the time I had three needles threaded and working at once—buff, red, and black—as I switched colors every second or third stitch. Doing it was almost enough to make me swear off working on even-weave ever again, but I did finally fight my way through it, and even I think it’s an impressive piece, and a good representative of what I do.

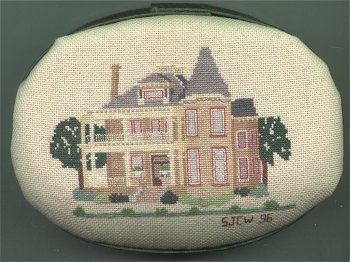

Although I started my next piece, an architectural of the house where we’d held our wedding breakfast in 1984, almost at once, I was FIVE YEARS finishing! It took me so long because I made the mistake of starting a picture full of grays and browns on a piece of sand-colored fabric, couldn’t tell the parts I had stitched from the parts I hadn’t, and wound up putting it down in disgust and despair for a couple of years. I finished it at last, but I promised myself never to get into such a low-contrast mess again. Despite all the sweat and eyesight it cost me, it turned out looking very nice.

More to come

If you haven’t already, please sign my